2021, owner’s tour

On the public DNS side, La Redoute acquired its first domain name in 1999, 23 years later, with just over 800 domain names – still with the same service provider – it was time to have an exact overview of the public DNS situation

After some archeology (email exchanges, old tickets, old-timers, …):

- The same entity manages both roles of registrar and provider (for 99% of domains).

- 800++ domain names with thousands of obsolete entries.

- thousands of HTTP web redirects.

- some protection products at the level of the registrar/registries (TMCH/DPML/Registry Lock/…).

- an incomplete API and GUI from the 90s.

From these 800++ domain names, ~180 were no longer used, but due to an unintuitive interface, the cleaning had not been done for a long time. The same was true for web redirections and DNS entries.

On the private DNS side, the platform is quite simple but still with the same limitations, errors and experiences.

Lots of obsolete entries, private IPs that end up on public domains (sysops, I know what you are thinking right now, but hey, the same problem on your side, right?), APIs are not necessarily usable, complete and/or up to date.

Which needs?

First of all, we have to keep in mind that at La Redoute, we are not intended to do IT, our job is to do e-commerce, so this service must therefore be offered off the shelf as much as possible.

Following this observation, some needs were identified for the public and private parts:

- automation of DNS zones/entries.

- optimize the budget.

- the possibility of having several providers for the same domain name.

For the public platform part, there were additional needs to be addressed:

- challenge our current registrar about their API, GUI, and pricing.

- challenge the possibilities of the different providers according to our needs by type of domain.

- possibilities of having HTTPS web redirections.

- automation of web redirections.

TL;DR registrar: We changed our registrar and in the process, it allowed us to save a significant amount of money for equivalent services.

Automation but which tools?

Coding an overlay to an API was quickly discarded because it means having to do it for each provider that we would like to use and also to maintain it.

A shortlist of libraries/tools remained:

-

- programmatically provision the resources you need

- keep a state of your deployed resources

-

- programmatically deploy and manage the DNS zones

-

- programmatically manage the DNS records

- lots of supported DNS providers

-

- programmatically manage the DNS zones

- mock ability

- few providers

-

- programmatically manage the DNS zones

- lots of supported DNS providers

- human-readable

Terraform is already widely used within technical teams; this choice would have been wise and quick to implement.

However, the chosen tool also had to be usable by non-technical teams if we wanted a full adoption of it.

It also needed the possibility of interfacing with other tools used internally (Terraform, Ansible, puppet, ExternalDNS, …).

That said, exit Terraform, denominator, dnscontrol, and lexicon.

After various phases of PoC, the choice turned to octoDNS (and spoiler alert, we will see that it has proven to be very useful with the new roadmap of the company).

Hello octoDNS

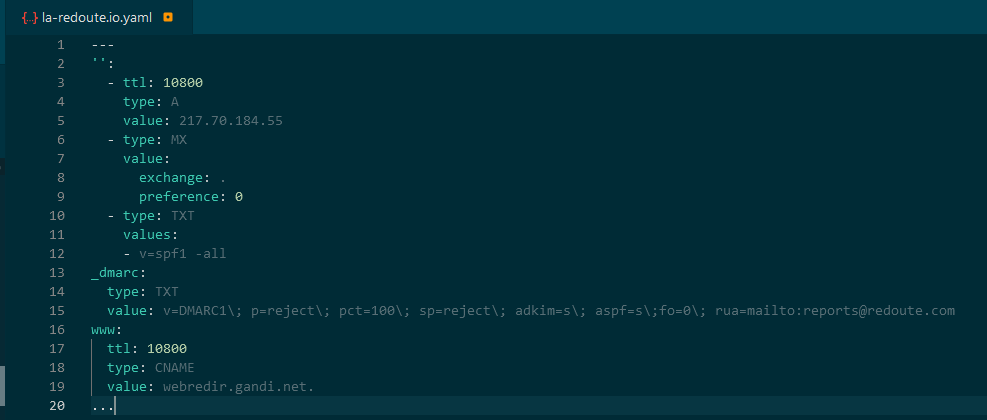

The pretty cool thing about octoDNS is its full YAML side. Everyone is or can be able to read, understand and write YAML files.Add some GitOps sauce, add the GitLab pipelines, and well-written documentation and we have found our happiness.

octoDNS is a project written in python that supports a multitude of DNS providers, and this is practical.

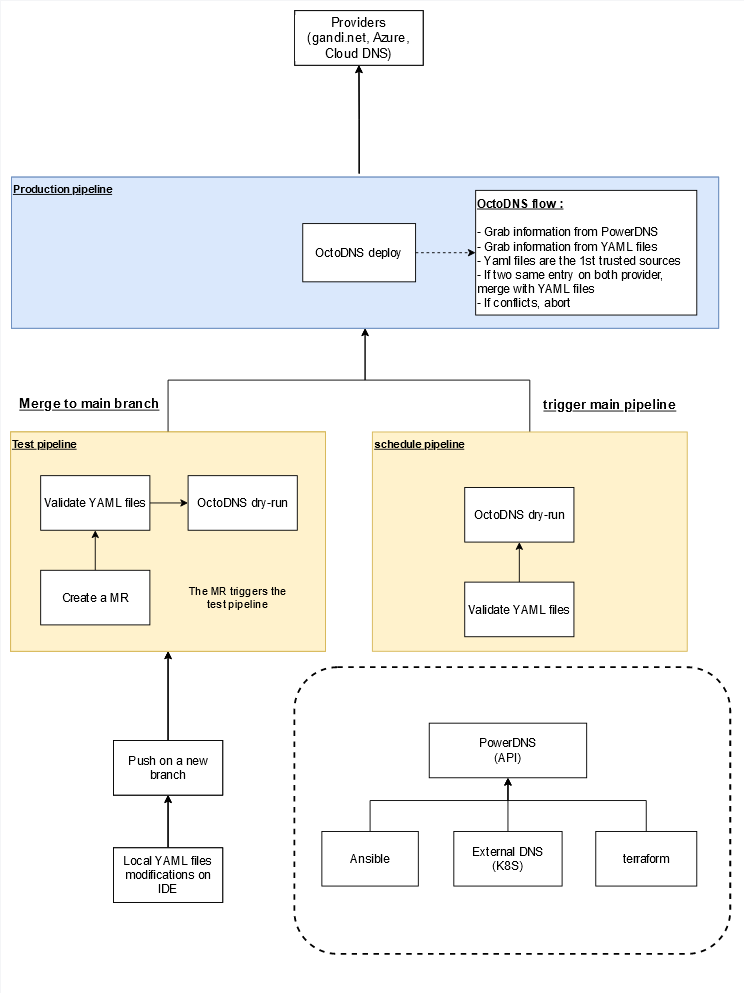

In real life:

- edit your YAML file

- push it to git

- grab a coffee

Concretely what it looks like:

- Add, update or delete your record

- through PowerDNS, if you are using IaC-related tools

- through the YAML file, if you are a human (or if you want to be sure that this entry will never be overridden because of the priority for YAML if the record exists on the two sides)

- If PowerDNS: grab a coffee, a cronjob will be scheduled, and if everything is fine, this will be pushed to production five (5) minutes later

- If YAML file

- Create a merge request from your branch

- Wait for the test pipeline to be successful

- Ask a teammate for approval

- Merge it to the main branch

- Once it is merged into the main branch, the production pipeline will be triggered and push the modification to the provider.

We chose the PowerDNS approach as a backend for our IaC tools because, you know, who wants to update a YAML file using terraform?

And this is what it looks like for the customer:

2022, REX

It has been 1 year since the migration of public DNS was initiated, and it tends to end soon. What caused the most problem was the migration of “exotic” TLDs – between the goodwill of the former registrar and the multitude of administrative documents to be provided or even notarized.

octoDNS has been very well received by technical and non-technical teams who use it. The job is done with proper documentation on how to use the GitLab webIDE and how to create an MR for using our deployment processes.

From a day-to-day perspective, there is no real saving time handling a DNS zone; the time saved must be 2/3 minutes at most.

The big change comes from the time saved during mass modifications of DNS zones, and this is a real game-changer. The fact of also being able to trace the changes and have a history of changes is a big plus. We can achieve that at La Redoute with the GitOps workflow and the Jira tool.

The process to create/update/delete a domain zone or a record zone is the following:

- Create a Jira ticket with an explanation of your need(s) – this is really important, because 10 years later, it may become very difficult to know why you have this record entry and/or domain.

- Changes are made to the zone within the Git repository.

- Merge request is created and linked to the Jira ticket.

- Pipelines are launched:

- success: approval is required before merging.

- fail: well, you have to rework your job.

- The main pipeline is triggered to perform actions to the provider(s).

The use of octoDNS also allowed us to start on the project of automatic renewal of public SSL certificates that are not held by LetsEncrypt.

Since the implementation and use of this workflow on public domains, octoDNS, and its stack have also been put into production for our private DNS infrastructure.

octoDNS, therefore, acts as a conductor for our various private DNS providers, whether on-premise or with a cloud provider.

And since a few days and the new roadmap, we know that it was a good choice and that it will save us a lot of time because we are migrating from one cloud provider to another.

On the DNS platform side, it will be quite simple: define the new provider to octoDNS, create your MR, grab a coffee, and voilà!